A couple of years ago I started trying to combine my rediscovered love of photography with my love of Circus. What you read here and see in the accompanying images represents what I have learned so far on the journey. I am by no means and expert yet. If you want to see some incredible images- my inspirations; pros I admire and would love to be able to equal one day- check out the work of Darin Basile or Todd Owyoung. What follows is the best advice I can give based on what has worked or not worked for me so far; take what you can use, ignore what you can't and please feel free to send me comments and let me know how I can get better. I shoot Nikon, so when I make a setting reference in this article, I will be using Nikon terms. I will try to translate where I can, but I am really only familiar with the gear I use. I started out (in this iteration of my photographic journey at least) with a D3200 and a 17-55mm/F2.8. These days that is my backup body, I am primarily shooting with a D4 and either a 24-70 or 70-200mm F2.8. All my lights are speed lights with various modifiers.

LIVE PERFORMANCES

|

| Capturing a Moment |

Let's start with shooting live performances- no second chances, if you miss the shot you miss the shot. It is always easier to shoot what you know. When you have the opportunity, watch the performance before hand without a camera in front of your face. Go to a rehearsal, see the show on multiple nights, whatever it takes. Knowing what to expect and when makes shooting much easier. Often, this isn't an option, but take it when it is. What helps me is that I am an aerialist and performer as well as a photographer. (at least I was until fatherhood and resultant increases in beer consumption came along) Even if I haven't seen a piece before, I can usually guess what's coming by watching the wraps, setups, etc. Pay attention to the music as well, it can give hints. (put those years of watching movies to good use- go ahead, sing the JAWS theme in your head... see what I mean- we all knew when the shark was coming) But really, see the piece first without a camera in front of your face if it is in any way possible, because the sad fact is that if you see an awesome moment through your viewfinder, it means you missed the shot. Conversely, if you captured the ideal moment, it means you weren't able to see it happen. There have been many shows where I got amazing shots, but had no idea what happened until I got home and started going through the images. So suggestion number 1 is - watch the piece first, then shoot. After all, that performer worked their tail off to create the piece you are shooting, enjoy the awesomeness.

If you can, shoot the dress rehearsal vice the formal performance. Without a paying audience present, you are much more free to move around and change angles. Also, DSLRs- even ones with "quiet" modes, are loud. Shooting a dress rehearsal means your machine gun shutter isn't going to disturb the paying customer in the seat next to you. You also won't have to worry about audience members blocking your shots or people in the front with their cameras blowing out your shots with their flashes. You also may get time to swap lenses out or even reshoot numbers, depending on how the rehearsal runs. The full dress is always the easier shoot if you can swing it.

Get familiar enough with your camera and the lenses that you will be using that you can make all the basic adjustments in the dark. Shutter Speed, Aperture, Metering Modes, Exposure Compensation, ISO - if you need to change it during the performance, you need to know how to do it without seeing the buttons. Don't count on your LCD display either, unless you are using a Hoodman Loupe or something similar, you want to keep that screen off as much as possible. You know those people who use their bright, shiny smartphones in the dark movie theatre? You hate those people right? Don't be those people.

If you have not been hired, or at least invited, by the company putting on the performance and someone is there who is shooting officially, stay out of their way. Don't follow them around and try to mimic all their shots. Talk to them beforehand if possible and ask where you can shoot from without getting in their way. This applies even if you are shooting at the request of one specific performer. (this courtesy also applies to any non aerial event you may be shooting, ask any wedding photographer about "uncle bobs")

Finally- Flash. I will mention this so often throughout the course of this article that you may wish to non-surgically insert a strobe into my body by the time you are done reading, but it is a pet peeve of mine. There are a couple of situations I will cover that call for using a flash when shooting aerialists, but in general, don't use one unless you absolutely need it and you have permission from the performer you will be shooting. Part of it is for safety of the performers (and your safety if the roustabouts catch you blinding their aerialists) and the other part is out of respect for the lighting designers. Someone put a lot of creative energy and artistic talent into setting up those lights and matching them to the mood, performer, music, energy and costuming for the routine. You should try to capture that part of the piece as well. Another reason not to use flash is that you can ruin shots of other photographers with your flash, just like they can ruin yours.

|

| This is what you get when someone else's flash fires during your shot. Beautiful right? |

Unless it is a daytime outdoor show, leave the speed light or strobe at home. (again- please, please, please, do not use a flash under any circumstances unless you have cleared it first with the performers you will be shooting. They are doing very complex, highly dangerous things for your entertainment. Blinding them at the wrong time- usually precisely the times that coincide with the best shots- can be lethal- and no, that is not an exaggeration. I am serious on this one.) Maybe you want a monopod depending on lens choice and multiple bodies/lenses if you have that option. (If the last few lines sounded like a foreign language to you or taking your camera out of program mode is a foreign concept, skip to the end where I give a translation and brief primer on some photography terms then come back - you did read the into- right?) If all you have is an entry to mid level DSLR with a couple of kit lenses, can you still get good shots? Sure, as long as the show is outdoors or well lit, but as the light gets dim you will quickly hit the limits of your gear.

|

| Entry level DSLR and kit lens, plenty of light. Works fine. |

|

| Entry level DSLR and kit Lens, hitting the limits of the system. |

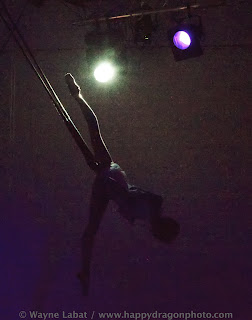

You're all packed, you left in plenty of time to find parking and get in as early as possible so you can find the best seat and angle to shoot from. If you are shooting in an official capacity and weren't able to make a rehearsal, ask if you can get in before the doors open so you can explore angles and see what lens/lenses you want to use. Look at the setup and see where the action will take place. Where are the rigging points, are there ground acts or will it all be in the air? See if the lighting guy is willing to show you his brightest cue, his darkest cue and an average scene so you can get an idea of the settings you will need. Whether you are there in an official capacity or not, talk to someone (ideally the stage and/or house manager) and find out where you are allowed to shoot from and where you aren't. If you intend to use flash (again, you really shouldn't) make sure this is allowed. Be polite and actually listen to what they tell you is allowed and not allowed. Respect them and they will return the favor. You may even find yourself getting better shooting access next time you are there (back stage, lighting booth, etc.) When picking where you will be shooting from, don't just think about your shots, think of the rest of the audience. They paid to see a show, not the back of your head/camera/butt while you shoot away. If you aren't shooting a rehearsal you will generally find yourself at the very back of the house behind the audience; although I once got stuck dead center front row where I needed a wide angle lens to get anything. If you are really lucky there will be a raised stage with a photo pit between the stage and the audience; common at rock concerts, but not circus. Depending on the venue, you may even want to keep a small ladder or kitchen step in your car in case you need to shoot over the audience from behind (or bring your stilts if you are a circus type - painters' not pegs for stability of course) Lens choice will be dictated by the size of the venue and where you will be shooting from, too much variation here for me to give anything more than gross generalizations, but if you aren't free to zoom with your feet then a zoom lens will be your best choice. As long as you can at least open wide enough to get a whole body shot of a performer at maximum extension (splits, etc) on the closest apparatus to you then you are good. I would say it is better to go too long vice too wide for most cases; you will be shooting fast and dark so there won't be a lot of detail to crop later even if you have a high resolution sensor. I often find myself right on the border between two zoom ranges. I started out erring wider, but I think after a bit of experimentation closer is the way to go. Of course, if you have multiple bodies, now is the time to break them out. You may have time to change lenses between acts if you know what’s coming, but you probably won’t want to change out during acts. Check your sight lines to all of the apparatus you intend to shoot. You are shooting aerialists, don't forget to look up. If the act is swinging, flying, spinning, etc make sure you have an idea of the arc of motion and the points of that arc where most of the action will take place. Sometimes, especially in tent shows or other temporary setups, there will be cables and guy lines coming down at various angles, this is the time to make sure none are between you and where you will be trying to get most of your shots. Also be on the lookout for follow spots and lights set directly behind where you are shooting into. One or two silhouette shots in a series make for cool variety. Nothing but 200 backlit silhouettes over an entire performance? Not as cool. This danger will also be more common in a tent show or other "in the round" venue.

Now you are set, let's talk about the different basic scenarios you might find yourself in and how to generically set up for them:

Scenario One- the "easy" one

It's an outdoor performance on an open stage. It's the middle of the day. There is plenty of bright sunlight streaming down, so bright you almost need your shades. This is partially deceptive. I say it's easy because in these conditions, there is enough light that anyone with any camera can get a useable image. You don't need high ISO, you don't need expensive, fast professional lenses, all you have to do is set a high enough shutter speed to freeze the action and go. Your basic DSLR and kit lens will be fine for this one. Even a phone camera will get something you can post on Facebook most of the time, unless the performer is doing a fast drop. But you don't want "useable" images, you want great images. This will be counterintuitive to a lot of people, but this is the time you want to - with permission of course - I think I mentioned that earlier, but it is worth saying again, always ask before you flash. (Come to think of it, that a good rule to live by even if you aren’t talking about photography) Now is the time to break out the speed lights, or strobes if you have them. Yes, shooting at high noon in the middle of the desert is when you want to break out that flash. Put a soft box on it, or a diffuser, but break it out. That nice, bright sunlight that lets you get away with slow lenses and low ISOs also creates really harsh, nasty shadows. What will set your images apart is using a flash to fill those shadows in. If the stage is open, with sky behind your performers and set your camera to Matrix metering. If there is a dark background behind the performer, use center or spot metering and meter off the performer. Set the lowest ISO you can for the prevailing light. Shutter speed it tricky here because of sync speeds. If you have High Speed Sync capability, now is the time to use it. It will lower the useable power on your speed light, but it doesn't take much to fill in the shadows unless you are shooting from way back with a long lens. Depending on your performers, 1/250 may not be enough to completely freeze motion on drops or fast spins, but it will be good enough for anything else. Generally speaking, when shooting with strobes, you use shutter speed to control the ambient light, aperture to control the effect of the flash. (if you really play with this enough, you can make a picture taken at noon on a bright day look like it was shot at night) If you have high speed sync available, you can set your shutter speed high enough to get the desired level of motion blur, or lack thereof, that you want. If you can’t use HSS, you will be pegged out at your max shutter sync speed to avoid blur. For all except really fast drops or high energy performers you will be fine. In bright daytime shows I find I am usually (ISO 100) anywhere between 1/250 - 1/500 sec and F8 - F13. I have a speed light on and High Speed sync activated with the flash set to manual. I have tried the TTL modes and have had mixed luck, I like manual better. Once I get a good basic flash power level dialed in I adjust exposure with aperture. There are only a couple of tricky things you need to watch out for. One is complacency. You can be cranking along with your exposures dialed in perfectly, then those pesky clouds roll past and you lose a great shot because the light changed. To prevent this I usually leave myself in Shutter Priority and let the Aperture adjust as the light changes, so I can control the motion freeze. This is also the only scenario where I don't generally keep a -0.3 EV dialed in. A little overexposure is ok, and I want those shadow details, so I go no exposure compensation or maybe a little positive, depending on what I see in the first few test shots. The second issue is that speed light recycle times suck. If you shoot a burst, you will only get a flash on the first exposure, so you really need to time your shots carefully so that perfectly filled shot is the one you want. Single shot is probably better than burst in this scenario. (If you are close enough that you can power down your flash and still get the fill you need you can improve recycle times or get one or two shots per charge) I use Continuous AF, I get the best results with nine point AFS-C lag setting 4 on my camera and I always use back button focus.

Scenario 2- The easy one

A big budget, professional show in a dedicated space with amazing lighting and hopefully a follow spot or three. Let's just imaging you are shooting Ringling, Cirque duSoleil, The Big Apple, Vargas, etc. It could be a small show that just happens to have great lighting and/or a follow spot for the performers. If they are traveling with their own tent you can probably assume that the lighting will be adequate for your purposes. This is actually the easiest case, if you missed the lack of quotes around the header. I don't mean simple, not by a long shot, but definitely enough light that for most acts you probably won't need to go to insanely high ISO numbers to get fast shutter speeds. It will probably be bright enough for any DSLR and Kit Lens to shoot fast enough shutter speeds. What you definitely do not need in this scenario (come on, say it all together now) is your flash. Just say no. In fact, most of these venues will announce something before the show starts about not allowing flash photography. Have I made this point enough times yet? You may think that flash is OK, I mean, it's just a little light, look at all these powerful spotlights that are already in the performers' faces, what's one more quick one.... Well, believe it or not there is a huge difference. Those lights are coming from a down angle and those follow spot operators are trained on how not to blind us with the lights. They are constant and as a performers we are used to them. What we are not used to is a bright, unexpected flash going off right up into our eyes during the micro-seconds we have to spot, track and grab the wrists or ankles of our partner, who has just flipped and spun out of our hands 20ft off the ground and will have a very bad landing if we miss. Off soap box now, just remember, flash is bad, M'Kay? Seriously, you won't need it. The main difficulty is the dynamic range of the scene. Especially if the performer is wearing white or other lightly colored costumes and the background is black. If your meter is seeing all the darkness around the brightly lit performer and if either you or the camera try to compensate for that, the performer will get blown out. The best way around this is to use spot metering and go manual. (or get really crazy and use an actual light meter) Meter and expose for the brightest part of the performer (not necessarily the face depending on the costume and light combo- if it's a white or silver costume, you might get better results metering off that) and leave your exposure alone, regardless of what the meter says, unless the light changes. For my camera, regardless of whether I am using a priority mode or full manual, I get the best results with -0.3EV dialed in. Your mileage may vary. If the lighting is good, I dial in the -0.3EV exposure compensation, spot metering, 9 point AF-C with a delay setting of 4, back button focus. I go full manual, find the shutter speed and aperture I like then turn my auto ISO on with a cap of 12,800 in case the lighting changes. (note on this- if I want to change the actual exposure with auto ISO on, I have to do it using the exposure compensation. If I just change Shutter or Aperture, the auto ISO will adjust to counter my and still average out the exposure. Takes a bit of getting used to if you are normally shooting fixed ISO). Since I don't have to wait for flash recycle times I also switch to continuous high speed shutter, focus + release priority, 10FPS. I haven't had a lot of opportunity to test this setup out; however, since most of the events I get access to are not as well lit. I do not use auto white balance for shows at all. If you are shooting raw, WB in camera technically doesn't matter, but if it's different shot to shot as the lighting changes, it makes editing harder. So pick one and stick with it so even if you get it wrong they will all be the same wrong and you can batch correct. I find that tungsten works best for normal stage lights, cloudy for LED lights, flash if the main lighting is from follow spots. I've not been lucky enough yet to shoot one of the big circuses. The image I opened this section with was from a large arena hip hop show I was lucky enough to shoot a while back. The image I will close with was from a local recital show that just happened to have a small follow spot. For comparison, the hip hop shot was taken at ISO 640, 1/250sec F2.8. The recital shot below was ISO 3200, 1/160sec F2.8. So there was quite a bit of difference in light available.

Scenario Three. The most difficult and also the most common

A dark show- in a club that has bad lights and no idea how to use the ones they have - or maybe a circus school that doesn't have a massive budget for lights or an experienced lighting designer. Seriously, I was shooting one show in a club and for the aerialist on silks they used a blue wash so dark that it was hard to see her with the naked eye, let alone a camera. Then the fire dancer came out and they lit her up with a bright white follow spot.

|

| Seriously? White spot for a fire dancer? Who does that? |

I almost had an aneurism. (full disclosure, this club has gotten a lot better over repeated shows, they actually had decent light the last time I shot there, it just took a year....) Anyway, for most of us not lucky enough to shoot Cirque for a living, this is the environment we will be working in. That isn't bad, it's actually fun and usually involves beer; but it is the most challenging shooting problem- and not just because of the beer. What lighting there is will probably be LED lights, which can be horrible for photography, as I will discuss in detail later on. It will most likely be insanely dim and focused for someone performing on the stage, not 15ft above it. My least favorite example of these challenges was shooting a double trap act on a portable rig set up on an outside stage at a local club. The stage lighting stopped almost exactly at the trapeze bar, so I got to choose which performer I wanted to expose for. The lighting guy figured the action would be ON the trapeze, not underneath it. You can see how blown out the feet of the base are compared how much darker the performer is just below the bar.

These shows, you pretty much do what you can. This is where the dynamic range and high ISO performance of your camera is really important, you need to shoot at the highest ISO setting you know you can get useable images from. If you have an actual light meter and a chance to use it before an act, you can maybe average the exposure so you keep both shadow and highlight detail, but chances are you won't have the opportunity. You will need noise reduction in post. For these shows, I leave the auto ISO on just in something nice happens with the lighting, but for the most part the ISO goes straight to the max I set, aperture goes as wide as the lens will allow, and I am lucky to be able to shoot fast enough to freeze motion. Anything slower than 1/250 and you will get blur on some drops and spins. So I find myself around 1/250 or 1/320, F2.8 ISO 12,800 for most of these shots. I leave the -0.3 to -0.7EV setting in if it is LED lighting (again, will have a whole section on LED lights later), 9 point AF-C with delay setting 4, back button focus. Pre-focusing whenever you have enough light to do so is vital. Continuous high speed shooting, 10FPS with Focus + release priority. Manual mode, spot metering, Auto ISO with a 12,800 high limit (high native for the D4). I shoot in shutter priority and try to keep above 1/250 sec unless it's a very slow routine. If the routine and music are slow, I will slow the shutter down, but only to about 1/120 or so. I use shutter priority so if it happens that there is a moment of unexpected brightness that lets the camera dial down the aperture and give me greater depth of field then it's a happy bonus, but pretty much it's gonna peg out wide open anyway. If the venue and the shooting location allow it, I will swap out the zoom for a faster prime to get the extra stop; it's worth it if you can do it and still get the framing right. Before I dropped the major coin for the D4, I was shooting with a D3200 and either a 17-55/2.8 or a 35/1.8. The highest useable ISO on that camera was 3200. I wasn't able to get great shots, but I was still able to get useable shots with the settings above. Other than the general darkness of the setting, there are a couple of big things to watch out for in these scenarios. First and foremost is that usually the LED lighting. The quick answer is that when you shoot under LED lights, underexpose 1/3 to a full stop. Whether you use exposure compensation or change it manually, underexpose a bit from the meter reading or you will get a lot of blown out images. Again, set a particular white balance and stick with it. For me, the cloudy white balance setting seems to be best for LED lighting. Second, other people will probably be trying to take pictures and they will be using their flashes. If you take a shot at the instant that someone tries to take a shot with their point and shoot, it will totally destroy your shot because your camera is set for the darkness. Their flash will totally blow out your shot. (see image above for demo of this) This sucks, but there is really nothing you can do about it. The last big issue is smoke. Clubs love smoke machines. I have a love/hate relationship with them. Sure, the smoke makes the shot look cool, but it screws with your autofocus and can make your shot come out fuzzy. Only way to deal with this is to pre-focus and take the shot. Once you get to post, take the black point setting up and it will knock the fog down somewhat. That's really all I've got for fog machines. I think the negative EV I keep dialed in helps as well. So- you are as wide as you can get on your lens, you have maxed out your native ISO, and you still don't have enough light to shoot fast enough to freeze motion. It happens. This is the one scenario where, despite all my railing against it, you may have to use a flash (with permission, of course) to get the shot. You may not think this is a big deal because everyone else's flash will be going off, but it really is. You are supposed to be the professional. Ask the performers first, explain to them that to get the shots they want, you may need to use a flash given how dark the lighting is. Respect their answer. Everyone in the crowd will be using the flash on their point and shoot or phone, but if the performer doesn't want you to use flash, then don't. If they let you, then go for it. If you can set the flash up off camera and trigger it remotely, do it. Set it somewhere high and point it down just like one of the stage lights would be. Whether it is on or off camera, set your flash to the lowest power setting that will let you get the shutter speeds you need and gel your flash. Use a 1/2 or a full CTO gel and maybe a diffuser of some type, depending on where you can set your flash or how far you are from the aerialist if you have to keep the flash on camera. A warm gel and the lowest possible power setting will still let you get as much of the effect of the stage lighting as possible while keeping your shots from looking like mug shots. Don’t use your popup flash. Unless you really know what you are doing and dial the power WAYYYYY down t’ll just make things worse. Trust me on this one. If you do need to use a flash, even on camera, use a real one. Unless you are using a flash, pretty much assume you will have to do a lot of work post shooting, brightening the images, pulling out noise and dealing with the LED washes and their fun effects on your shots. And sometimes, no matter what you do, the light just sucks for photography, you do what you can and take what you can get because the shots are cool.

Final note before I leave the live performance arena- although this is true for any shooting scenario. Don't forget to look around you, some of your favorite shots may have nothing to do with what is happening on stage. Photography should tell a story, sometimes beautiful things happen off the main stage.

|

| This is one of my favorite shots, random girl dancing to a DJ between aerial acts at a festival. |

|

| My favorite assistant, hard at work. The chains were his idea, and wound up working really well, thank goodness for child labor ;-P |

|

| A good assistant is vital - and this model has a fan for life. |

A little bit of spin can make the difference between a perfectly lit image and a horrible shadow cast by the apparatus covering your perfumer's face- and the performer really can't do anything to control that. Next is how fast you get the shot. Models on the ground can hold an awkward post for as long as it takes you to set your lights, frame your image, shoot, check the LCD, make adjustments, reshoot and repeat. Aerialists- not so much. If we look like we're having an easy time holding a pose in the air, it's because we have trained for years to fake a smile while we really feel like our shoulders, hips, knees, or other other body parts are screaming for mercy and about to tear themselves out of our bodies. Trust me, even if we make it look easy, it isn't. It hurts. And if we hear you say, "perfect, just hold that a second more while I get the lights right," one more time, then after we fall on our heads onto the crash pad, we may walk over and shove your meter into an inappropriate body orifice. In our gym there is a great shot of me in a heel hang on a trapeze bar. That photographer was shooting in burst mode and what you don't see on the wall are the next three frames which chronicle me falling from said heel hang onto my head.

|

| "just hold it a second longer...." (I am the model in these images, so I know this scenario from both sides of the camera) |

|

| Or fall out of it.... maybe we should have used a crash pad.... safety third! |

We'll do what we can to get the shot, we're professionals and sado-masochists, but really, we do have our limits. Set your lights and your shots up before putting us in a horribly painful position and asking us to hold it. Trust me, we'll thank you. On to lights. Use studio strobes if at all possible. Speed lights will work, but the recycle time sucks. For a model on the ground those seconds of recycle between shots may be inconsequential, but it seems like an eternity when you are holding a difficult position in the air. Also, if your session consists of your performer running a routine while you shoot, you will miss lots of shots while your speed lights recharge. Strobes recycle faster and have more power. Use them if you can. If you are stuck with speed lights, make sure your performer knows they may have to expect a second or two wait between shots. If you can set up so that ou are shooting at less than full power, do it. That way you get multiple shots per charge (depending on your power level) or shorter recycle times. Whatever lights you use, don't forget that your model will be farther off the ground that your usual subjects. You will either need very tall light stands, or something to set your light stands on to get more height, because you still want the light to be coming from higher than your subject to avoid horror lighting. Also, don't forget to throw in some side or rim lighting to set your aerialist off from the background. Costuming and Makeup. Most performers should have a good selection of costumes and an idea of what works with their body type and coloring. Same for makeup. Get help with these things if you need it. Just be aware that most performance make up is designed to look good from the cheap seats in the balcony and handle crazy stage lighting. Your performer will probably not have to go so heavy on makeup for studio shoots. If they do want to for a particular look, just make sure they cover all the exposed skin so there is no line you will have to fix later. The one thing you can't go overboard on is powder. Have plenty; apply frequently. Your model/aerialist will work up a sweat holding all the poses you want to shoot and they will start to shine. Shooting angles. If it's a controlled shoot, you get to set this up however you want. Unless you are going for a specific artistic effect, I think your best bet is to shoot level with your performer or slightly higher. Depending on your location this may be as simple as going up a staircase, or you may have to bring your own stepladder or borrow one from the aerial gym. Shooting upwards on purpose can give some interesting perspective, but in most cases it will lead to a distorted image. Finally- rigging. Maybe I should have covered this first, but the article didn't flow that way. Ideally, you bring your setup into the performer's aerial gym and use rigging points that are already there. As a photographer, if you aren't an experienced aerial rigger, don't assume you know what you are doing. Just because that lighting truss in your studio can hold a 200lb speaker, don't assume it is safe to hang a 125lb aerialist from it. If you don't know what you are doing with rigging, get help from someone who does. Aerialists- if you walk into a photographer's studio and see a rigging point- don't assume that photographer knows aerial rigging. Ask the question and if it looks sketchy, don't hang from it. Otherwise you may get a great image of a horrible disaster. That's pretty much it for studio. As long as the rigging is safe and you understand how difficult it is to hold the poses you want the aerialist to hold for your shots, studio work is studio work. I say that lightly, but this is probably my weakest area as a photographer. I just had a friend, who is one of the most amazing photographers I know, take a look at my first studio aerial session and give me a lot of advice on how to make it better next time. So this part may wind up getting a revision in the near future.

SOME GENERAL THINGS: (topics applicable to multiple scenarios above)

PERFORMERS:

In general, newer performers tend to rush through their acts. Don't expect them to hold poses for any length of time. With experienced performers, it depends on their act and performance style. Circus style performers will generally do more pose holding than aerial dance style performers. The dancers will still hold poses, but it will only be a beat or two. (these days the line between Circus aerial and Aerial Dance is a quietly shifting, blurry maze; but in the not too distant past, mistaking one for the other could cause fights) Some performers do a fast paced act all the time. One of our local performers is famous for this, she goes by the stage name of Mango and I joke that I have to remember to set my camera to Mango Speed for her performances because she is a very high energy performer. For most of Mango's numbers, if I shoot less than 1/500sec things are gonna get blurry. This is pretty much twice the shutter speed I need for most routines; however, she is also a very experienced performer and knows how to hold poses when she can in her routines. The more experienced performers (circus style at least) will generally hold the good poses long enough to give an audience the chance to appreciate the pose and applaud. This also gives you a good amount of time to get the shot. The newer performers will tend to rush and won't hold the good poses for that beat you need to get the shot. Know your performer and calibrate yourself accordingly. Listen to the music as well, if it is fast with a killer beat, you will have to be faster on the shutter than for a slow, lyrical piece.

CHIMPING:

This is a derogatory reference for the act of looking at the image on your LCD after every shoot. You look like a chimpanzee exploring a new toy that fell into its' zoo enclosure. This is a horrible practice to get into for several reasons. The worst one is that you will miss a lot of shots while you are looking to see how the last one came out. Also if you are shooting a live show and you are in the middle of the audience, each time you look at that bright screen you are disturbing people around you. It's pretty much equivalent to someone using their cell phone in the movie theater. You should be shooting primarily out of your viewfinder. If you like shooting in live view mode using your LCD, get a hoodman loop or other similar device to cover it. Otherwise, turn off the image preview function that normally brings each image up on the LCD as you shoot it, you only want that screen to be active on demand when you need to see something on it. It's ok to check the screen after the first couple of shots in each act, especially if it's a drastic lighting change since the last act, so you can adjust your settings as necessary, but really, after those initial test shots and adjustments, once you are dialed in, there is no need to look after each shot. You either got it or you didn't. Chimping won't help, it will only make you miss the next shot while annoying your neighbors.

TWO EYED SHOOTING:

A good technique for any sort of action photography, this means shooting with one eye on the viewfinder seeing what the camera sees, the other remains open to see what is happening on the rest of the stage. This is easier for me when vertical shooting rather than horizontal. It is almost impossible to do if you use your left eye as your viewfinder eye- at least it is the way I hold my camera. It takes a lot of work to get used to, but it really helps for large group numbers, letting your focus in on a particular piece of the action and shoot while still being aware of what is going on around the rest of the stage. Practice this one and see what you can do with it. I can generally pull it off for around 20 minutes tops before I start getting a headache, so I only use it for group numbers.

LED LIGHTING:

LED lighting is the new thing. It's cheaper than traditional lighting and doesn't get as hot. Most LED stage lights can change color easily as directed by a controller. These factors make them the go to lights these days, especially in club environments and lower budget theaters. From a lighting designer point of view, LED stage lights are an epic win. For a photographer; however, LED lighting is a horrible evil creation designed to make our lives a living hell. Especially the RED LED, which is look much loved by clubs and theatre designers everywhere. Traditional theatre lights are tungsten. They put out fairly warm, white light which is then modified as necessary with gels to change the color. Despite the colored gels, there is always a little bit of the whole spectrum that gets through, even if the eye can't perceive it. So a red wash with Tungsten lights still has minimal amounts of the full spectrum in it. Not so with LED lights. Multi-Color stage LED lights are made up of 3 or 4 different channels. Most have some Red, some Green and some Blue diodes. Some add a 4th color, but I am not really sure how that works. The bad side for photography is that when an LED light is set to show a single color, that is ALL that light puts out. Digital camera sensors all have a set amount of Pixels, or light gathering sites, on the sensor. Each sensor site can only record the levels of one color out of the three primary light colors- Red, Green or Blue. The predominate color in the human visual spectrum is green, so camera sensors are weighed to reflect this. 60% of the pixels in a typical camera sensor are green detectors. The other 40% is divided equally between blue and red sensors. Whereas a single color wash with old school tungsten lights would still contain undertones of all the other colors, a single color LED wash contains ONLY that one color and nothing else. That means that, best case being a green LED wash (which you almost never see) you are only getting to use 60% of your camera's sensor capability. If the wash is red or blue, you are only using 20% of the sensor capability. (red is the worst, because it is the opposite color from green, blue at least is closer so isn't quite as evil). This problem gets compounded because the light meter in your camera expects the light hitting it to be full spectrum. So if it sees only a single color, it sees that as how much light it is. So it sees the scene appears anywhere from 40 to 80 percent darker than it actually is because of those unactivated sensors and recommends a much higher exposure than you need. If you are following the advice I gave above for scenarios 2 or 3 and are spot metering off the aerialist- your meter will give you bad info when you are shooting a single color LED wash, especially red. It will read the scene as much darker that it is to your eye, and your subject will be totally blown out when you look at the images later. This is one of the reasons I find that leaving the negative exposure compensation set in my camera helps. If I know there will be heavy red or blue LED washes, I may drop down to -0.7 or even a full stop. If I am lucky, this will give me enough room to keep from having blown out highlights and I will be able to fix the color cast somewhat in post.

Other color LED lights are minor evil. Plan accordingly and be prepared to have to do more work in post production. I find selective color luminance and saturation adjustments are the best ways to correct these images. Sometimes playing with brightness or white balance can help. If all else fails, as a last resort you can try converting the image to black and white and trying different filters, this will sometimes save an otherwise unsalvageable shot.

FOG MACHINES:

Fog looks really cool with stage lights. It makes for some great effects. But it comes with some drawbacks. First off it makes things more difficult for your autofocus. This really can only be helped by pre-focusing and locking, or manually focusing on the subject if the AF can't work through it well enough. Second, it makes your images a lot less clear than they appeared when you shot them. Not a big deal, usually the effect is pretty cool, and I have found that taking the exposure down a bit in post and raising the black point a bit will knock the fog effect down, if not completely out in post production.

Don't get too bent out of shape if the majority of the images you shoot don't live up to your expectations. What you see online represents someone else's best work, their highlights. You don't get to see the images they didn't like. When I first started out shooting performances, I was lucky if 1 of every 10 shots was a keeper. Now I am around 1 in 5. I am also shooting a lot less these days. When I started, I was getting about a thousand frames for a two hour show, now I am down to around five hundred. So in the couple of years I have been doing this, my keeper rate has gone up fourfold. I am also learning how to work better in post. I figure as long as I learn something from each mistake and I get better with every show I shoot, then that's enough. Just remember, things don't always turn out as planned. For example- this was supposed to be a short piece for an online journal, not the epic tome is has become.

Unless you are doing only the bright daylight thing, you will have to work up your images after the fact, at least to remove noise. I mostly use an aperture plug-in called Noiseware because it allows me to batch process images, which is much better than doing them individually when I have a hundred shots and not a lot of time. I usually group by ISO ranges and process each range separately because you don’t need as much for the lower ISOs as the higher. The goal is to do the least processing possible to generate an acceptable final result. Over reduce the noise and the images look plastic. Even with minimal processing, once you have done it a few times to your own images, you will start to recognize the slightly creamy look of images that have had noise reduction work done on them. I do the noise removal last because in my method it results in creating a TIFF of the image. I understand Lightroom has awesome noise reduction built in, I will be experimenting with LR as a future project to see if it is worth converting over. For now my workflow goes something like this-1) Get home, no matter how late, immediately get the images from the card onto the computer, then start a backup before I go to sleep.2) When I get home from work the next day and the backup is done, I make an initial scrub and star the images that are good enough to bother working up.3) I go back through that list of starred images and start doing exposure, black point, color and crop adjustments as necessary. By the end of this pass I will have decided what the final group of images I am going to put out will be made up from. If I have time and she is willing, my girlfriend provides a second set of eyes and a new perspective. Often she will point out things that I missed “just trust me, that shot, while well lit and technically perfect, makes her look fat, she will hate you…” She is always right.4) I end with noise processing on this last set then post them to wherever I need to.5) Other than noise reduction and minor corrections, I try to do minimal processing on shots from live shows, since I want them to be as true to life as possible. For studio shots I will process to whatever extent I need to depending on the intent of the shoot. Shouldn't have to worry about noise, at least, if you're doing it right in the studio though.

CAMERA RESET:

Finally, one last tip. You just finished shooting for several hours in the dark, your lens is wide open, your ISO is cranked up to the max. Don't forget to reset your camera back to your normal shooting settings, or the next shot you try to take of your kid in the park will be blown out and be totally overexposed. Not that I have made this error more than three (maybe 10) times or so....

FINALLY- THE TECHNICAL JARGON EXPLAINED:

ISO:

ISO stands for "international standards organization," and in photographic terms, it means how sensitive your media is to light. In the old days, you had to pick this in advance, different films had different ISO ratings (also known as film speeds) and once you loaded a roll into your camera, you were stuck until you took it out and put another in. Digital cameras let you can change this setting on the fly. Your sensor doesn't change, but changing the ISO rating on your camera settings changes the sensitivity at which it records incoming light. The higher the ISO number is, the more sensitive the sensor will be to light. (ie- in a bright, sunny day with plenty of light, you would use something like ISO 100 or 200. The darker your environment, the higher the ISO number you will want to use- I frequently shoot at ISO 12,800 for aerial shows) The trade off is that the more sensitive you make your medium, the more noise you capture. Noise is basically graininess in your image, in other words, a loss of detail. This is where you generally get what you pay for in terms of cameras. The higher end cameras can shoot at much higher ISOs with much less noise. I used the terms full frame and crop sensors as well, this is literally the size of the sensor array in your camera. For a given resolution (number of pixels- which is an actual measure of how many individual capture sites there are on the sensor- 16 megapixels, 24 megapixels, etc) the larger the sensor size is, the larger the individual capture sites will be and the better they can capture light. This is a very oversimplified explanation, if you want more details and lots of insane math and physics, hit up google. Otherwise take my word for it. A 16mp point and shoot has a really tiny sensor. A 16mp crop sensor DSLR (known as DX in the nikon world, not sure about others) has a much bigger sensor. A 16mpx full frame (FX in Nikonese) has an even bigger sensor. For Nikons, the full frame sensor is 1.5x larger than the DX crop sensor. (If you wonder why it's called Full- that means it is pretty much the same size as a frame of 35mm film) In general the crop frame DSLRs will be the lower end less expensive camera bodies. The sensor size also changes how the lens works with the camera, but that is way too much detail for this article. While there are some crop sensor DSLRs out there that have awesome high ISO capabilities, in general for any given resolution the full frame will be better in low light. And yes, I know your point and shoot or iPhone low light camera may claim to have high ISO capability, the sensor is so small your image will be uselessly noisy. So you can put a visual with the concept, and because I like finding excuses to show everybody pictures of my supermodel son, here is an example of a low versus a high noise image.

|

| ISO 100 - with flash, effectively no noise - and isn't he cute? |

|

| ISO 204,000 - still cute as hell, but also incredibly noisy - the picture, not him. |

The second image is so noisy it is pretty much useless, I just took it because my son is cute when he sleeps and I wanted to really test the low light capabilities of the D4 when I first got it. This was taken in a pitch black bedroom. The only light was a street light outside filtered through blinds. Noisy as hell, but I still got the shot. Try doing that with your phone.

There is more to noise than just ISO, proper exposure and the types of colors and contrast of the scene you are shooting also play into it, Google if you want to know more, I quickly get lost in all the math and physics that are needed to explain it more fully.

LENSES.

DSLRs and some point and shoots have interchangeable lenses. (the part that the lens attaches to is called the Camera Body) Lenses fall into two basic types, primes and zooms. Basically, zooms zoom, or change their magnification, primes don't. I am specifically referring to optical zoom. Digital zoom is just manipulation after the image is on the sensor. It is basically an in camera crop and enlarge, just like you would do on your computer after the fact. It lowers the apparent resolution of your shot. If you have a 16mp camera and you use 2x digital zoom, you now have an 8mp camera. Optical zoom is a function of the lens elements physically moving and will always give a better result because you still get the full resolution of your sensor. Lenses are rated first in terms of focal length. Primes will only have a single number- i.e. 50mm, 35mm, 200mm, etc. Zooms will have a range- i.e. 24-70mm, 18-55mm, etc. The second rating on a lens is called F-Stop. Prime lenses will always have a fixed F number- 50mm / F1.4, 35mm / F1.8, etc. Zooms can either have a fixed F number- 24-70mm / F2.8 or a range- 18-55mm /F4.5-5.6. If the number is fixed, that means it stays the same no matter where you are in the zoom range. If there is a range, it follows the zoom range, meaning at the lowest zoom you will be at the lowest F number, and vice versa. The F number means Aperture (yeah, it should be A, don't ask me why, I didn't invent the language) and is a measure of how big the opening is inside the lens that lets light through to the camera sensor. The smaller the number, the bigger the opening. The bigger the opening, the faster the aperture. Therefore, when I refer to a "fast" lens, I am talking about how wide the aperture is and how much light it lets in, not how fast it zooms or focuses (although those are other important factors). Most professional prime lenses have F numbers of 1.2 or 1.4 (although there are some good 1.8 primes out there) at least for the focal lengths used for our purposes. Professional zooms are all F2.8 for our focal ranges. (if you get above 200mm that changes, and sigma just put our an F1.8 zoom for crop sensors, but that's outside of this discussion). So lower F numbers = faster lenses.

SETTINGS:

Taking your camera out of automatic is a necessity for shooting circus or dance. The auto or program mode just isn't designed to keep up with what we need to shoot. So here is a very brief and simplistic description of the various camera settings I mentioned in this article and what they mean for you. These are things you can- and should- control on your camera:

ISO- we beat that one to death earlier. Higher is more sensitive to light. Most point and shoots default to setting this automatically and you have to go into menus to change it. Most DSLRs default to fixed ISO and you have to change it manually unless your camera has an auto ISO function you can turn on. You camera will have a range of ISO settings. What you really need to know is which of these are "native." Basically, the native settings are actual sensor differences, the rest are computational tricks- just like optical versus digital zoom. You want to shoot within your camera's native range. On my camera, for example, the native range is ISO 100 - ISO 12,800. If I shoot at the highest native range, ISO 12,800, there will be noise, but I will be able to pull it out in post. My camera will let me go past the native range, all the way up to ISO 204,000, using processing tricks internal to the camera. Yes, as seen above, I can get a shot at those higher ISOs, but it will be incredibly noisy and I will not be able to clean up the image in post. If you are a photojournalist who has to get the shot and a noisy shot is ok to publish in the Times, it's all good, but for out purposes, find out your native range and stick within those boundaries. Also, know your camera and test it out. The D3200 has a high Native ISO of 6400, but I found that in practice I had to shoot it at 3200 or lower to get useable images.

SHUTTER SPEED- How long the shutter allows light to fall onto the sensor. Shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second, with a higher bottom number meaning a faster time. IE- 1/200 or a second versus 1/2 a second. Faster shutter speeds are required to freeze the motion of a performer. If you have tried to shoot a performer or anything else moving and it came out blurry, you probably used to low of a shutter speed.

APERTURE- the F number (or F-Stop) mentioned in the lens discussion. The lower the number, the bigger the opening and the more light reaches the sensor. The other side is something called depth of field, or how much can be in focus at any time. Lots of physics again, but basically the wider the opening (the smaller the F-Stop) the shallower the depth of field. If you have ever seen a picture where the main subject is in focus but everything in front of or behind them is blurry, this is an example of shallow depth of field (or a crappy instagram filter, but on real shots its' a function of the F-stop). If you see a landscape image where everything from the front to back is in focus, that is a high F-Stop and a small aperture.)

WHITE BALANCE: For those old school people, different film chemistry would record light differently. If you have played with instagram filters or some camera app settings that emulate different types of old film, one of the ways they do this is by altering the white balance of the image. Digital sensors can record at different white balance settings, sometimes called Color Temperatures, or just Temperatures. These are numbers, listed in degrees Kelvin, or K, and referred to comparatively as warmer or colder. Daylight is generally considered Warm (having more red/yellow tones) and is roughly 3200K. Flash is generally colder (more blueish) and around 5600K or higher. Fluorescent lights have a more greenish case. What this setting literally does is to tell your camera sensor what is white in a particular scent. The camera then adjusts all other colors based on what you have told it to view as white. These different color temperatures are why your pictures look weird and have strange colors if you are shooting in mixed light. (i.e.- you use your flash in a room mostly lit with regular lightbulbs). Typical settings on a camera are Tungsten (the classic lightbulb), fluorescent, flash, sunlight, or cloudy. Most DSLRs also let you set a custom white balance, but if you are messing with that, you probably aren't reading this section anyway so I won't get into that. Again, check your manual or google for details on how to set your particular camera.

RAW/JPEG: These are different ways you can record an image. (I said record for a reason. Your camera always shoots in raw, but unless you are set to record raw files, it will automatically concert that raw image into JPEG or the file type you have set and discard the extra information) Google away for more information and a lot of controversy on whether you need to shoot raw or not. Basically, shooting raw (and each camera has its' own file format it calls raw) just means the camera records all the data it sees at the instant it shoots and doesn't do any processing really before it sends the image to your computer. JPEG, which is what most point and shoot cameras record in, means the camera decides how to initially process the information before it records it. This means smaller images, but it also means you lose some of that data that the camera decides to process away. There are other formats, but those are the main options. See your camera manual for what yours can do. In general, raw gives you more options for fixing mistakes later on, but the files are much larger. If you have the option to shoot raw, do it. You will have to convert the files later on your computer, but its' worth it. Unless they have a specific reason to shoot JPEG most pros shoot in raw. The downside is that you will need a program on your computer that can handle the raw images your camera records. That is where it gets interesting, because raw formats are camera specific. Not just brand specific, but specific to individual camera model. Adobe has a raw format called DNG (digital negative) that they are tying to make standard, but so far there is no common raw format. For Nikon cameras, they will be .NEF files, but each camera's .nef will be slightly different. If you are on a Mac, as long as you have an updated version of pretty much anything out there, even iPhoto, you should be able to import and view your raw images just fine. If your camera is very new, it may be a month or so before the software updates catch up.

LIGHT METERS: This can be an external toy, or even an app on your phone. If you have one of those you probably have some idea how to use it. But all DSLR cameras have built in light meters. On a nikon you see this on the bottom of your viewfinder. It's a bar with 0 in the middle and little blocks that light up to either the left or right of zero. No blocks lit on either side = you are set for what the meter thinks is the right exposure for what you are aiming it at, depending on the meter mode you have set. As blocks light up to the left, the meter is saying you are underexposing (too dark). As blocks light up to the right, the meter is saying you are overexposing (too bright). Depending on your setup each block represents a portion (usually 1/3) of a stop. If your meter is set to the correct mode and pointed at the right spot, then as long as you are within a few blocks either side of zero you are probably fine. Some people prefer to slightly overexpose, I prefer to generally slightly underexpose, spend enough time with your camera and pay attention to the meter an you will learn how those dots on the meter translate into recorded images and you will find your sweet spot. For now, it's enough to know that if the dots are on all the way to either side of the meter, or the meter is blinking at you, you probably aren't going to be happy with the outcome if you take the shot without changing something. In case you were wondering how the meter on your camera works, the cliff notes version is that it takes all the image data it sees in the area you have selected to meter (matrix, center or spot) and compares that to an internal database and tries to figure out what it is seeing and adjust the exposure for what it thinks is neutral for the closest match it finds in that database.

METERING MODES: This controls how much of the frame your camera uses to determine exposure with its' internal meter. I use the Nikon again because that is what I know. The choices are basically Matrix- which tries to average the whole frame light readings, Center Weighted, which uses a relatively large portion of whatever is in the center of your viewfinder (or centered around your selected focus point- read your manual to know for sure how your camera does it) or Spot- which is much smaller spot either at the center of the viewfinder or focus point. Some cameras even let you specify different spots for determining focus and exposure, but you will have to consult your manual to see how yours works.

FOCUS MODES: There are many different names for specific modes, again depending on your specific camera. Basically they boil down to Single or Continuous focus as the main categories. Single focus means when you press your shutter halfway (or your focus activation button if you use back button focus) the lens will focus once and stay at that focus setting until you either take a picture or let go of the button and press it again. Continuous focus means as long as you hold the shutter halfway down (or you keep your focus activation button pressed) the camera will continually shift focus to stay on whatever your designated focus point is aimed at. There are too many different varieties of modes and numbers of focus points used on different cameras for me to try and break down, again you need to get familiar with your own camera. Any DLSR and Lens combo should also let you focus manually.

BACK BUTTON FOCUS: Most DSLRs have the ability to set this up in one form or another. Basically what it means is you set another button (usually on the back of your camera) as the button that activates your focus mechanism instead of the shutter button. This is a very commonly used technique by sports and action photographers. It takes some getting used to, but once you get used to it you probably won’t go back to shutter button focus. The advantage of this technique is that the camera doesn't try to re-focus each time you press the shutter button. This means you experience less shutter lag, and it also very handy for low light settings like most circus shows. The way you use this is by focusing with your focus button where you know the action will be while there is light, then you leave the focus alone unless your subject moves. No matter how good your camera is, it will have a harder time focusing the darker the scene it. So with back button focus, you can focus on that fabric or trapeze bar while the lights are bright, then leave it alone and shoot away without losing focus when the lights dim. (if you use it, just remember you are set up this way if you hand your camera to someone else to take a picture for you, otherwise you will get an out of focus shot because they all expect the shutter button to make the camera focus)

PRE FOCUSING- Using either manual or back button focus. When you have enough light/time to focus, you find the spot you know the action will be, focus on that, then leave the focus alone and snap away when the action happens. You can’t do this if you have the autofocus keyed to your shutter. Also, once you have your pre-focus set, don't mess with it unless you need to. I just screwed this up on a shoot today and lost two shots that would have otherwise been the best out of a three hour shoot. I am still sort of kicking my own butt for this. Luckily, some of the other ones were pretty good.

HOW CAMERAS FOCUS- There are different types of focus sensors, your camera probably has two different types. Google if you want the really technical details, but for our purposes, just trust me that in general the more central the focus point is in your viewfinder, the more accurate it will be. The ones on the edges are generally less accurate. But even the most accurate types require some sort of contrast between what you are trying to focus on and the background in order to work as well as a certain minimum amount of light. So if you are trying to focus in the dark on a performer in a dark costume, you are asking the impossible and your lens will probably HUNT (keeps trying to find focus and never locks, constantly moving) If at all possible, try to focus on any spot there is good dark/light contrast, even if that is somewhere else on the stage that is the same distance from you as your target but better lit .

SHOOTING MODES: P does not stand for professional. It stands for program. That means the camera selects everything for you. This will generally not work out well for performance situations. Some cameras have different scene modes (Night, Sports, Portrait, etc) which alter setting for these general situations, but if you understand the settings you can get more control going into other modes or manual. So what are those other modes?

SHUTTER PRIORITY: You pick the shutter speed that you want and the camera adjusts the aperture to match it.

APERTURE PRIORITY: You pick the Aperture and the camera adjusts the shutter speed to match it.

MANUAL: Just like it sounds. You set both the shutter speed and aperture you want.

EXPOSURE COMPENSATION: If you are using a mode besides full manual, the camera will try to set whatever values you leave it to control so that the resultant exposure will match what it thinks is correct. If you find you need the resultant shots brighter or darker, Exposure Compensation tells the camera to change its' thinking accordingly. Positive EC means the camera will record the scene brighter than it thinks it needs to, Negative EC means darker. This is usually measured in terms of "stops" or more likely, fractions of a stop.

STOPS: Not really a camera setting, but a measure of the combination of settings that equals a given exposure. Really super basic user level definition- the textbook correctly exposed image is the 0.0 point for any given frame- the ideal amount of light. Half that amount of light is -1.0 Stop. Twice that is +1.0 Stops. "Stopping down" means making the image darker. "Stopping up" means making it brighter. The three major settings which you use to change the Stop of a shot are ISO, Shutter and Aperture. All three are tied together. ISO 200 is one stop down (darker) from ISO 100. 1/100 shutter speed it one stop up (brighter) than 1/200. Wider apertures (lower numbers) translate to higher stops- F1.4 is one stop brighter than F2.8. Basically each full stop of change halves/doubles the amount of light reaching the sensor. So- assuming you leave ISO the same, an image shot at 1/100 of a Second F2.8 would have the same brightness as an image shot at 1/200 of a second F1.4. The first one would have a slightly deeper depth of field, but would not be as effective at freezing motion. The second would be better at freezing motion but have a much smaller area that was in focus. There are always trade offs for any given shot, it is up to the photographer to determine what is the most important area in any given setting.

FLASH SYNC SPEED: Shutters on cameras aren't always an on/off state. Basically, there are two "curtains" on your shutter. One moves first, the other second, with a slit between them exposing the sensor. For any given camera, there is a maximum speed at which the entire sensor will be exposed simultaneously during a frame. If you use a faster speed than this, the second curtain will start closing over the sensor before the first has completely opened. In normal lighting and shooting situations this isn't an issue. If you are shooting something really fast, like a race car, using a faster shutter than this "max sync speed" (which is usually 1/200 - 1/320 of a second depending on your camera model) you may see that round things like wheels become ovals and objects get a little stretched. This is because as that slit of open space moves across the sensor, the object moves, so it is in a different location as each portion of the sensor is exposed. Not really problem in most cases. Where it becomes an issue is when you are using flash. The burst of light from a flash or studio strobe is insanely short, sometimes on the order of 1/10,000 of a second. As long as you are shooting slower than your maximum sync speed, this isn't a problem, because for that 1/10,000 of a second (or whatever your flash fires at) the entire shutter is open, so the light from the flash hits the entire sensor. If you are shooting faster than your max sync speed (most cameras actually don't let you do this, they will stop you even in full manual mode when they sense a flash being used) then only part of the sensor will be uncovered when the flash fires, so you would wind up with black bars across parts of your image. In other words you actually see the shutter curtains.

Some cameras have a mode called High Speed Sync (for Nikon) or something similar. When using a flash that supports this option it stretches out the length of time the flash fires over so that there is a long enough burst of light to expose the entire sensor. The drawback is that to fire over a longer time the flash has to reduce its' power. The longer it needs the burst of light to last, the lower effective power it will be able to use. So you will get less range and power out of your flash (and use up batteries faster) when using high speed sync.

THE END:

This article is already way too long, if you want more just hit a Google Search near you or the photography section of your local library or bookstore but you should at least be able to use these explanations to translate the rest of the article above. Or, if you really liked this article, I have recently expanded it and turned it into a book, check it out here.

One last note- no matter what you are shooting with, or how long you have been shooting, read the manual for your camera. Even the pros do this when they get a new camera, it may surprise you what cameras can do these days.

No comments:

Post a Comment